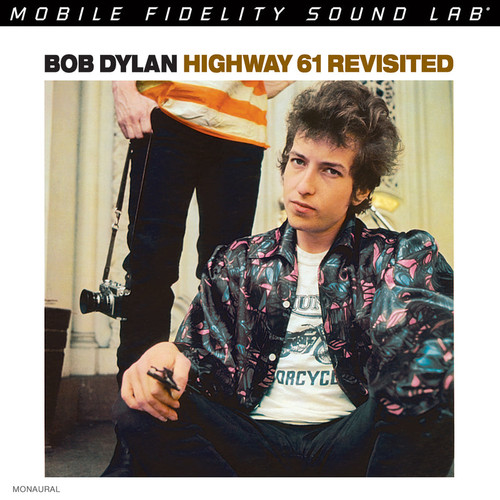

Mastered from the original master tapes and limited to 3,000 copies, this mono hybrid SACD reissue illuminates Dylan's emotional condition – he laughs in the midst of songs, experiences a few false starts, hits a couple of bum notes, occasionally sings as if he's stumbling down a Manhattan sidewalk after having one too many at a smoky pub, prizes rawness over perfection – with microscopic accuracy and unparalleled directness. The preferred mix at the time of the recording, the mono version presents Dylan as he and his producers originally intended. Since the separation of the stereo versions isn't as sharp, this mono edition places Dylan's vocals in the heart of the musical action and as one with the accompaniment. It paints listeners an incredibly accurate portrait of the attention-getting, concrete mass of sound that features no artificial panning and straight-ahead immersion into the music. This is how almost everyone first heard this timeless album – making the mono mix all the more historically valuable and truthful.

The uninhibited joie de vive is discernible in the rattling piano lines on "Black Crow Blues," seemingly subconscious ramble of the hysterical folk rhyming of "Motorpsycho Nightmare," bluesy dream sequencing throughout "I Don't Believe You," and intentionally out-of-tune yodeling during "All I Really Want to Do." On a majority of the prized set, Dylan lets his guard down, but does so in clever manners that speak to his surrealist imagination and biting wit. He possesses the rare ability to make planned strategies appear spontaneous, to challenge audiences with stinting wordplay and minimalist melodies that provide a deceptive false security.

And so the apparently autobiographical and self-aware "My Back Pages," one of the earliest examples of Dylan's immersion into symbolist prose and abstract metaphor, remains controversial for its on-the-surface denouncement of his earlier condemnations of social institutions and injustices. Peeled back, the tune is a brilliant release – an essential escape hatch for Dylan to both relieve himself of unneeded pressures and distance himself from pundits. As an indelible piece of art, it succeeds in masquerading obvious meaning while simultaneously forcing listeners to question their own actions.

As is the trifecta of relationship-themed compositions that closes the record, as well as the eternal "Chimes of Freedom," the standard that journalist Paul Williams dubbed Dylan's "Sermon on the Mount." Its inseparable conjunction of apocalyptic imagery, personal emotion, allusive lyricism, balladic alliteration, and inclusive sympathy signaled that, having already eviscerated the rules associated with pop and folk music, Dylan had just begun his assault on our consciousness, making Another Side of Bob Dylan that much more mysterious, unequivocal, and requisite.